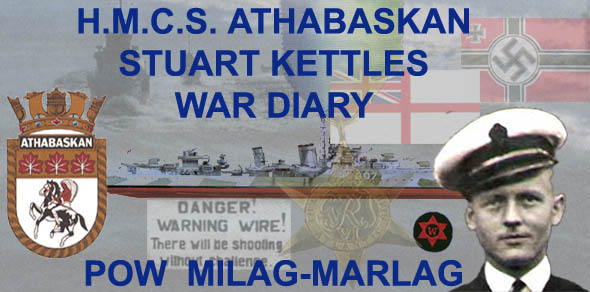

H.M.C.S ATHABASKAN G07

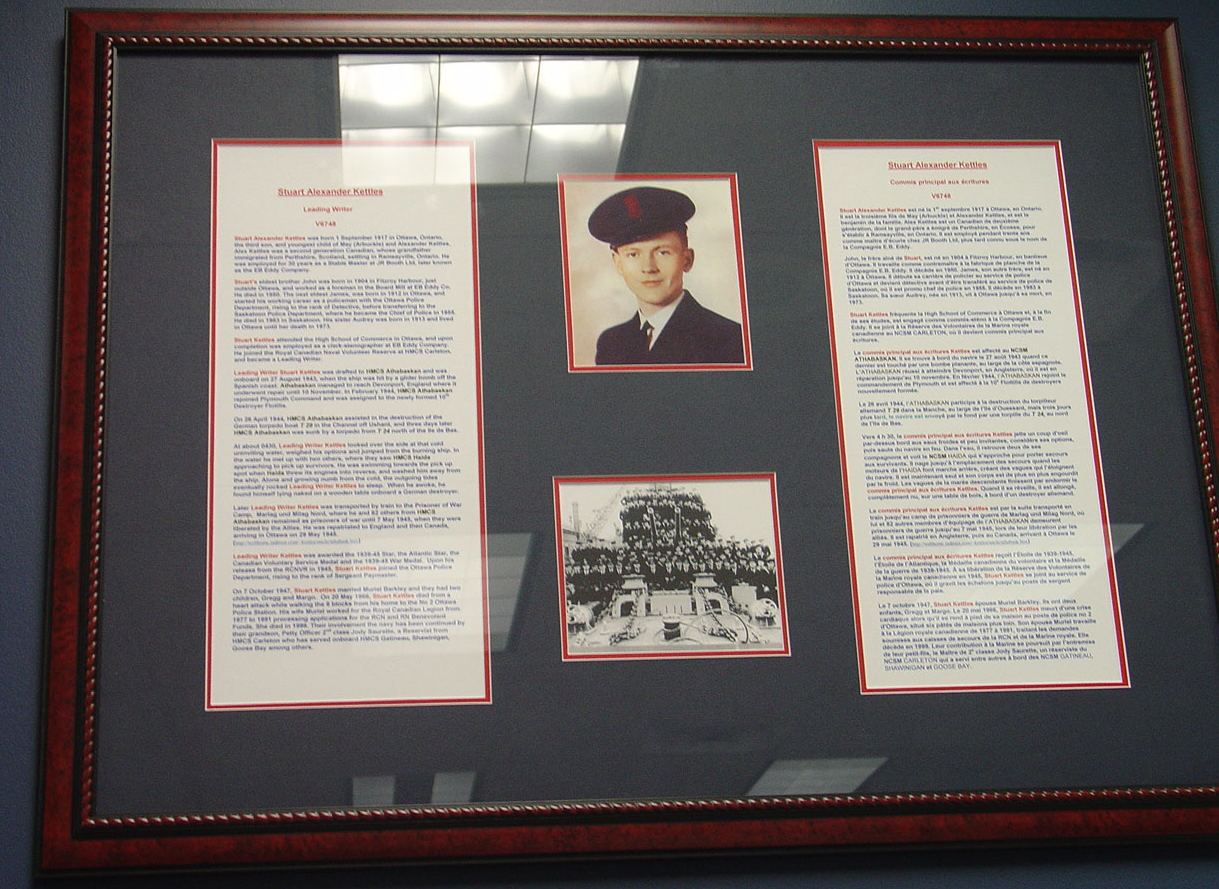

Stuart Kettles, Leading Writer RCNVR V-6748

and all the men who served onboard a ship in

the Atlantic during WWII

My uncle was a member of the Royal Canadian Navy Volunteer Reserve and served on board H.M.C.S. ATHABASKAN a Tribal Class Destroyer which was sunk off the French Coast on April 29 1944, subsequently he was taken as a POW and was detained at Marlag und Milag Nord, which is located at Westertimke, in the northern part of Germany.

When he was transfered to the POW Camp, the Canadian Y.M.C.A. distributed

A Log Book to all POW's so that they could, if they wish record their experiences

as a POW, sketches, poems, short stories of importance or humour.

The following are a few excerpts from my uncles "War Time Log Book" written in his own words

He also wrote A Poem about the Athabaskan while he was a POW

*********************

THE FLYING BOMB ATTACK ON HMCS ATHABASKAN

The above body of water, with the date, are two items that, like the previously detailed experiences, will remain with other memories in some remote corner of my mind for quite same time to come. It was the middle of July 1943, that we had completed a minor refit to the bow of H.M.C.S. ATHABASKAN and after a few trial runs to determine whether or not she would be able to take it or not, were informed that we would proceed to the Bay of Biscay to carry out a patrol. The nature of the operation was to prevent German submarines from returning to their base for repairs, re-fuelling, re-ammunitioning, etc., their course taking them through the Bay, their destination being the great German underground submarine base at Brest, France. From the time of departure from our operational base at Plymouth England, until our ultimate return, usually covered a period of from seven to eight days, our patrolling speed being from 12 to 15 knots.

On our first patrol, a number of Spanish fishing vessels were encountered outside their 3 mile territorial limits. This aroused suspicion and on investigation they were found to be collaborating with the Germans in that they were informing them by radio of our every movement. When this bit of information had been uncovered, the crews of five of these fishing vessels had been removed from their ships and the ships sunk. The Spaniards who had been on board were taken back to England with us and turned over to internment officials. We continued to carry out these patrols, and on one other occasion picked up five German submarine survivors, their submarine having been sunk by a patrolling Sunderland flying boat of the Royal Air Force.

Only one more thrill greeted us during the monotonous days we spent in the Bay. One evening we received a report from an R.A.F. plane that there were five German destroyers about fifty miles ahead of us. There were only three of us, an English destroyer, a Polish destroyer and ourselves. Our Captain was the Officer in charge of our flotilla and he immediately passed the order along to give chase. Immediate preparations were made in case of action, hammocks were lashed to the bulkhead to prevent flying shrapnel, benches were lashed down to keep them out of our way in the even of manouevering at high speed, also numerous other precautions such as checking guns for elevation and depression, firing short bursts from the Oerlikons to clear the barrels, making certain the ammunition hoists were in good working order.

At 1700 we went to action stations, the engines were revved up to full speed, and we stood by waiting for the word that would send us into action. All night the chase went on, the sun greeted us in the morning like a ball of bright red wool and it wasn't until 1000 the next morning that we had to abandon the fun and give up, having received an order that the German ships had escaped under the cover of darkness, into the French coast. For approximately six weeks we had been kept on this monotonous patrol, forever searching and seeking but finding nothing. However, little did we know that soon we would find more than we had ever anticipated.

As usual, we returned to Plymouth after being relieved by another flotilla, and immediately set about to replenish our supplies, also re-fuel, This took about three days, during which time it was hoped that we had seen the last of the Bay of Biscay, but we were doomed to disappointment, We learned that once again the Bay would be the scene of another of our operations, but there seemed to be an air of tenseness and expectancy lingering about. The reason for this was unknown at the time, but I later found out that on this trip the British Admiralty had been informed that a large number of German submarines were attempting to reach the aforementioned submarine base at Brest (France) and it was our job, along with numerous other flotillas equipped for anti-submarine warfare, to destroy as many as these submarines as possible.

At approximately 16.30, 4:30 P.M., 25th August, 1943, we left Plymouth for the same old spot. We arrived and commenced the patrol of our particular area at about 1000 the morning of the 26th August. All day long we swept so many degrees one way, so many degrees another, but we accomplished nothing. Perhaps you say, "What a waste of time". Maybe so, but orders are orders and they must be carried out. It was not until the next morning, 27th August, 1943, at approximately 1030, that we received the first indication of approaching excitement. At this time, a secret order was received on board to the effect that we could expect to be attacked by German aircraft carrying a secret weapon. One Officer from each ship was to be detailed to observe and note this weapon, it's action, how it was released from the plane and any peculiarities noticeable. Immediately, the crew was ordered to "Defence Stations" and after my arrival in the Chart House, spotted the signal and noticed that the secret weapon to be expected was called a flying bomb.

At the usual time we had our mid-day meal, after which our time was our own, for the crew at "Defence Stations" changed at 12 noon. It was a beautiful day. The sun blazed down in all it's glory, the water, a magnificent colour of blue, was like a pane of glass. Most of the crew off watch lay on the upper deck doing their best to get a nice sun tan. All was serene and quiet, only the rush of water as it slid by and the steady throb of the engines broke through our musings, or I should say, half sleep. We were in a world of our own for about half an hour, but suddenly revived to a world of reality and war. The shuffle of many feet on the iron deck, the dull ringing of the "action stations" bell from the engine room, a rough shake along with the excited cry "ACTION STATIONS" turned the once peaceful surroundings into a typical beehive of activity.

The crew raced to their respective positions for in the Navy absence from your action station is an unpardonable sin. In a matter of seconds, we were all set to see what Jerry had in store for us, and it didn't take long to find out. Over came twenty enemy aircraft, Junkers and Fokke-Wolf "Condors" and immediately we heard the angry roar of the 4.7" and 4" guns of our own ship. The time was approximately 1255 when the action began, and at 1305 it was all over as far as we were concerned. Jerry got one of his flying bombs to work. It struck us on the Port Side just aft of the bridge, passed through the Chart House, the Chief and Petty Officers mess, down through the Starboard Flats, out through the Starboard side and exploded in all it's fury about twenty feet clear of the ship. As it went out the other side, the fins sheered a signalman's both feet at the ankles. He stayed conscious long enough to apply tourniquets on himself. His name was Charles Kent and he was from Calgary.

All the starboard side of the ship from the bow back to the break of the foc'sle was completely stove in. "A" and "B" guns were put completely out of action, the barrel of Starboard Oerlikon gun Number 1 was twisted like a piece of wet rag. All communications from, the bridge were shattered, the lights all over the ship were out, and it must be admitted that confusion reigned for a few minutes. Fire broke out in the Stokers' mess, and the ship was doing everything but sinking. We were given the order to get out on the upper deck, and no time was lost in carrying this out. The ship by this time had a terrible list to Starboard and everyone was ordered over to the Port side to try to counteract this. It had little effect, but it all helped. Meanwhile, everyone kept nervous and anxious eyes scanned for enemy aircraft which might come back and try to finish us off.

The fire in the Stokers' mess was finally squelched, but the biggest job was still ahead. Volunteers were asked for to go down into the Torpedomen's mess and shore up the ship's side so we could try and get back to port. About six of us went down to slog, slip and swish around in a mixture of dirty, heavy black fuel oil and salt water. Mess tables floated, lockers that had been torn loose by the concussion along with hammocks and odd bits of clothing also floated around. From down there the damage looked much more severe than could be seen from the upper deck. She just looked like one huge hole and this had to be plugged in order to keep the ship afloat. Anything we could get our hands on was jammed in the holes - hammocks, overcoats, underwear, boots, broken lockers, splinters off the mess tables, hats, socks, and everything was soaked with oil. As you got down to plug a hole, the ship would take a slow, weary roll, and a shower of cold, salt water would hit you, almost taking your breath away, but you couldn't quit, you had to go on in order to get back to port. You worked until you were ready to give up. Reach for something, lose your balance and down you go. Get up, wipe the oil off your face and the salty taste off your lips and try again. It seemed so hopeless you felt like crying. Officers worked with men for it was a case of all or nothing, and it is at times like this when the Officers really forget their ranks and get to know the worth of the men, of the real honest-to-goodness every-day guy.

As others came down to help, you finally got a chance to get a welcome rest. On reaching the upper deck, you asked for a cigarette, someone else offered you a cup of tea to try and steady you down. Gee, it felt good, but why don't you get moving and get out of here. However, the oil is badly contaminated with salt water, which must be cleared up before you can get under way. At last, after about one and a quarter hours, we finally got under way at a very slow speed possible - five or six knots. You moved for ten or fifteen minutes and then find yourself stopped again. More trouble with salt water in the fuel oil. Everyone had a dose of nerves, some swore at our helplessness, others moved about as though in a trance.

The inside of the ship looked as though a miniature tornado had struck - you couldn't move without stepping or tripping over something. Emergency lanterns swung from the deck-head, casting eerie shadows about. Occasionally the narrow beam of a flashlight could be seen as the doctor or his assistant moved around through the wounded, eighteen in all. Some were lying on tables, some more were on benches, others littered the upper deck by the Sick Bay, The stench of antiseptics, blood, yes, even the oil, mingled together to cause a very nauseating odour. The injured showed badly torn flesh, deep gaping wounds from flying shrapnel, broken legs, even to the extent of both feet blown off. Some had teeth blown out by the concussion, others suffered abdominal wounds. Minor injuries consisted of bad bruises, punctured ear drums or nerves.

From my action station, the only indication at the time as to the severity of it all, was a blinding flash of flame as the aerial torpedo exploded. We were hit at approximately 1305, on the 27th August, 1943 and did not arrive back at our operational base in Plymouth, England, until 2130, 31st August 1943. To make it more clear, and for comparison sake, it took us only eighteen hours to reach our theatre of operations, whereas it took us 104.5 hours to get back. The trip back was heart-breaking. Our water supply was gone, therefore no washing, no shaving. The only food on board was that in the Officers galley. Our meals consisted of nothing more than a sandwich and if we were lucky, a cup of tea to wash it down. On orders from the doctor, any of us who had been down in the Torpedomens' mess shoring up the ship's side, had to discard our shoes, socks, and out our trousers off at the knees. This was a precaution against oil burns.

For a little over four days we had no sleep. Those of us who were still on our feet gave what assistance we could to the doctor in looking after the wounded. As the fuel tanks on the port side were emptied the oil from the tanks on the starboard side had to be pumped by hand to the tanks to the port side. This was necessary in order to try and alleviate the list to starboard - the side of the ship suffering all the underwater damage. Can you picture the crew as we finally hit port? - filthy, dirty, unshaven, bloodshot eyes from the hot sun and lack of sleep, trousers out or torn off at the knees, some in bare feet. Yes, it was quite a spectacle, but such are the consequences when you are on the losing end of a battle at sea.

During our return voyage, five of the crew were buried at sea. Perhaps you are curious enough to want to know what this is like. It is a lonesome and sad picture. Chaps you have worked with, slept with, eaten with, kidded and fooled around with, have died in defense of those they love. A spare hammock, just a rough piece of ordinary canvas is located. The body is laid in the hammock; a number of empty shell cases are placed around him. The hammock is lashed around the body, and if a White Ensign is available, that too is placed around the body. The body is carried to the rail of the ship. There, the Captain reads a short piece from The Bible, says a short prayer, and the body is dropped over the sides. This ceremony certainly provides one with plenty of food for thought.

Such was the only incident, outside of our P.O.W. time, that will remain a vivid memory for some time to come. Eventually it may pass from my mind, but until it does, I have taken this means of remembering those five good Canadians who gave all any man could be asked to give.

Those boys are:

| A. Latimer | Acting Petty Officer |

| P. Prudhomme | Leading Cook (S) |

| J. McGrath | Able Seaman |

| W. Pickett | Able Seaman |

| W. Smith | Able Seamen |

Underwent extensive refit, due to bomb damage in August. From September - mid November we had Radar, Asdic and Gun trials followed till the end of November, then based at Scapa Flow. Operated off the Norwegian coast in attack against enemy merchant shipping in convoy with Royal Navy Battleships H.M.S. ANSON and the French Battleship "RICHELIEU",Aircraft Carrier "ILLUSTRIOUS", Cruisers H.M.S. NIGERIA, H.M.S. ALGERIA and eighteen Destroyers. Proceeded to KULA BAY RUSSIA, on convoy duty with American "Liberty " ships. Speed of convoy - six knots. Picked up convoy off FAERO ISLANDS. German Cruiser SCHARNHORST sunk about sixty miles from us on return voyage with empty merchant ships. We were dispatched to escort the cruisers in the SCHARNHORST battle, but owing to engine room trouble, continued on to FAERO ISLANDS where Christmas was celebrated. Round trip took twenty eight days. One possible enemy submarine to our credit on this trip.

It was now about 4:30am 29th April, 1944. I looked over the side at that cold uninviting water of the English Channel by now covered with thick, dirty, fuel oil. My first thought was "Gee, I can't jump into that", but when I turned around and looked at the burning ship, which was beginning to settle to her watery grave, I suddenly decided, "Hell, I can't stay here neither". There was no shock when you hit the water, but it wasn't very doggone long until we soon realized that it was no Turkish Bath.

The next time I saw the welcome rays of sun was quite different. I lay on a wooden table naked as the day I was born, shivering from the cold immersion. I asked where we were, the answer "On a German Destroyer"

On arrival at the interrogation camp after four days on a train, we were herded into small cells. Only one man in a cell. Each of these cells had one small

window with iron bars on it. In one corner was a wooden bunk with a straw mattress on it. The mattress cover was made of similar material as potatoe bags. We

each had two very thin blankets, which were far from adequate, owing to the weather being very chilly during the night. Around 8am the next morning, the long awaited

breakfast finally arrived, along with it, bitter disappointment, for the food consisted of two slices of bread with jam, but no margarine, and a cup of ersatz tea,

barely enough to tease a good appetite. For the next 28 long days and nights our meals were

BREAKFAST 8AM:

2 slices of black bread, with jam no margarine, or vice versa, 1 cup ersatz tea.

DINNER 12:30

1 small bowl of soup and 3 - 4 potatoes with skins on.

SUPPER 5pm:

Same as for breakfast.

While we were in solitary confinement for interrogation, we were suppose to get 3 cigarettes a day, however, the Germans method of counting seems to be different

from ours, for we often missed. After one week and a half I got my first session of interrogation, which lasted 2 and a half hours, and was carried out by an Officer

of the Gestapo or SS.

After 3 and a half weeks the Germans decided that we must have teeth to clean, and they gave us a tooth brush and some kind of tooth paste.

Believe me it was a real treat to feel your teeth and mouth reasonable clean after not being able to clean your teeth for nearly a month.

Shortly after this marvelous experience, my friend the Gestapo or SS returned, to see how good my memory was. This session lasted for only about one hour, for after he

called me a liar, I got mad, and in 5 minutes he left me alone. For a while I thought my minutes of breathing fresh air were about to be numbered, but the Officer

angrily stalked out of my cell, and I wasn't sorry.

In each of the rooms there were twelve men. Around the walls there were two-tier wooden bunks, with the same old straw mattresses and two blankets. We had a muster three times a day, at 9am, 2:30pm and at 7pm. Rain, snow, sleet or blow we had to muster, sometimes we stood for half an hour or more, until they counted us all.

In the early days of our captivity ferocious, trained police dogs were employed to guard the prisoners but by judicious, surreptitious use of food and petting their ferocity melted away. One day the German guards entering the barracks were shocked to find several of their man-eating dogs lying under the bunks with the men licking their faces. The guards promptly posted a notice in English that the dogs were absolutely forbidden to accept food from the prisoners. As Germany's manpower dwindled younger guards were sent off to the army, replaced by aging veterans of 1918. When food packages for seamen arrived at the village three miles distant, a detail of POW's was sent under these guards to bring them in. The walk frequently proved too strenuous for the decrepit jailers and seamen would carry their rifles for them and give them lifts in the carts. Before arriving back at camp they would help the guards from the carts, button their tunics, smarten them up and generally hand back their rifles, to make sure they would not be replaced by younger, hard-boiled guards.

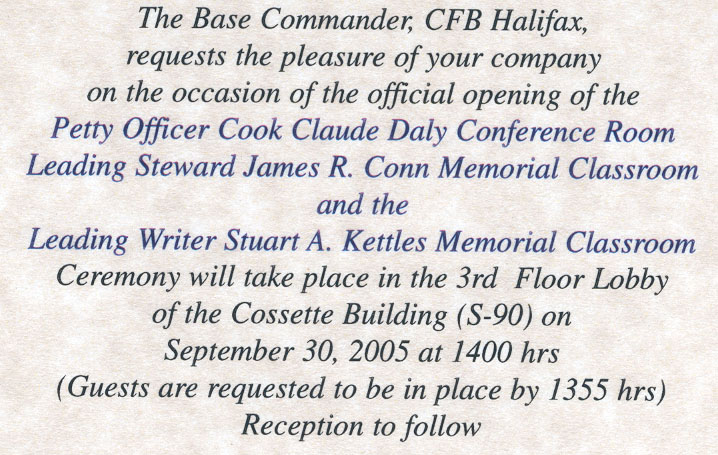

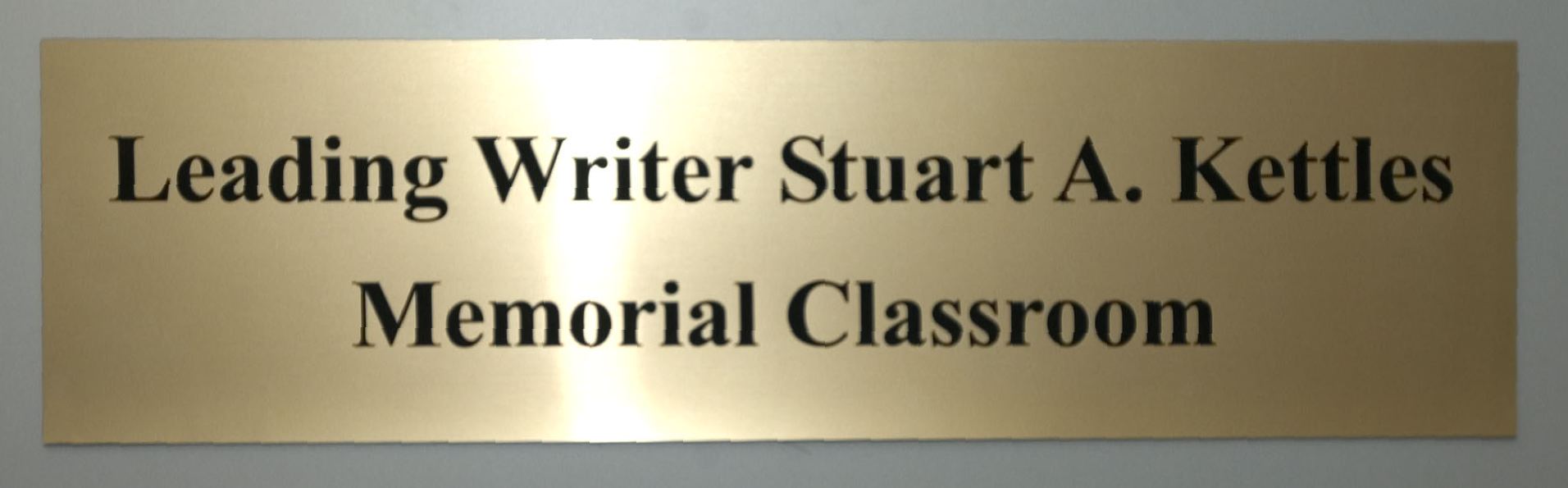

On September 30, 2005 three class rooms in the Cossette Building at CFB Halifax were renamed in honour of Second World war sailors.

The three men were Leading Writer Stuart Kettles, Leading Steward James Conn and Petty Officer Cook

Claude Daly.

PO Daly served on H.M.C.S. ASSINIBOINE and L/Steward Conn served on H.M.C.S. ESQUIMALT

:

The City of Ottawa in 2005 launched a street-naming initiative to honour our local veterans. Stuart was chosen as the 2017 veteran to have this honour bestowed upon him for the service he has given to his country and the city. This event took place at the Canadian War Museum during the the Candlelight Tribute for Veterans Ceremony.

Left to Right: Chief Petty Officer 2nd Class Jody Saurette, Mr. Bruce Kettles, Mr. Al Smith, Ms. Margo Smith (nee Kettles), His Worship Jim Watson,

Councillor Mark Taylor, Mr. Scott Saurette and Mr. Devon Saurette.

Ships the Athabaskan worked with on Patrol & Convoy Duty

Description of POW Camp Marlag Milag

In June 1941 Russia and Britain found themselves in alliance against Germany.

As a result Britain agreed to supply the Soviet Union with material and goods via convoys through the Arctic Seas .

The destinations were the northern ports of Murmansk and Arkhangelsk. To reach them, the convoys had to travel

dangerously near the German occupied Norwegian coastline. My uncle took part in Convoys JW55A and RA55A in December of 1943.

After the war there were many commemorative medals issued by various governments, of these,

only one was approved for wear with real medals, The Queen did approve the Russian "40th Anniversary of Victory in the Second World War"

gong, and it so appears in the Canada Gazette. Known locally as the Murmansk medal because a number of RCN sailors on that convoy were eligible to receive one.

A sideline story not involving my uncle entitled "The Greatest Convoy Disaster" can be viewed.

When parcels were sent from Canada to POWs in Germany, the sender filled out a Parcel Contents list

which accompanied the parcel. When the POW received the parcel he could then check the contents to ensure that everything was still there.

He would then sign a Conformation Received Post Card which would then be return to the sender.

The Canadian Government at Christmas time would send each POW a Christmas package of personal items that they could use in their daily routine.

A copy of the Government Christmas card and the mailing envelope can be viewed.

For the complete Glider Bomb Attack of August 27, 1943 and other Athabaskan stories Athabaskan Stories

There was an article published in the Spring of 1996 edition, Vol 5, No.1 of the "Canadian Military History" Wilford Laurier University, Waterloo, Ontario, presenting the scenario that the Athabaskan was sunk by friendly fire.

If you wish to learn more about the Athabaskan or the Haida go to

Canadian Tribal Association

H.M.C.S. Athabaskan

H.M.C.S. Haida Naval Museum

Francis Roach an Athabaskan Survivor

SA Francis Roach

An RAF Airmans exploits from WWII and as POW

Airmans Diary

An RAF Airmans war time log account as a POW and surviving the "Death March"

The Death March

Naval Museums in Canada

The Naval Museum of Manitoba

The Alberta Naval Museum